Thermostable Peroxygenase from Thermophile’s Self-Sufficient CYP

Another look at the brilliant research that molecules from Fluorochem are applied to. This time advances in more stable, more practical, biocatalytic methods, using cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), led by recently qualified PhD student Matthew Podgorski, from the laboratory of Stephen Bell at the University of Adelaide. This paper builds on a series of studies from Bell’s group, including recent ACS Catalysis and Chemistry Europe papers, where Fluorochem-supplied fatty acids and aromatic substrates were used to probe CYP enzyme activity.

Enzymatic biocatalysis continues to make great strides in chemical synthesis. Increasingly applied to difficult transformations, it is producing results in a more sustainable manner than many traditional chemical techniques. However, to practically use enzymes in larger scale or industrial applications requires these proteins to survive long stretches at ambient temperature, or even retain activity after heating cycles. Enzymes derived from thermophiles are an obvious source of biocatalysts that can operate at higher temperatures, don’t require cold storage and are generally more robust, often being more resistant to organic solvents or other extreme environments.

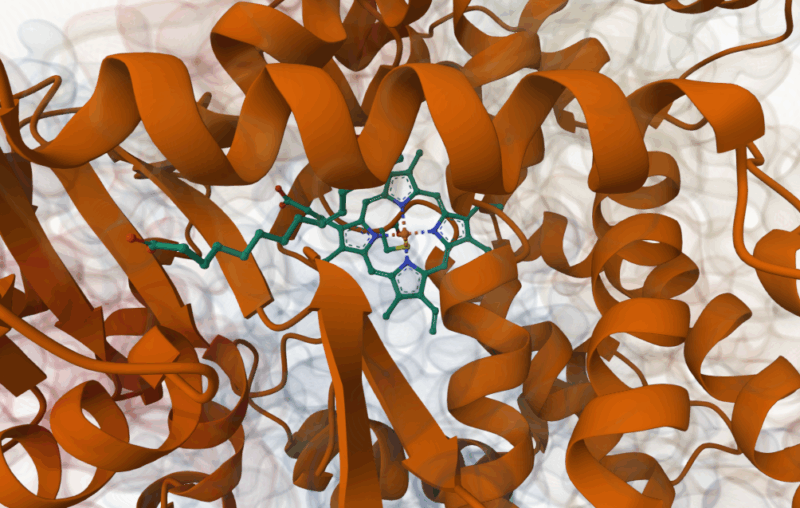

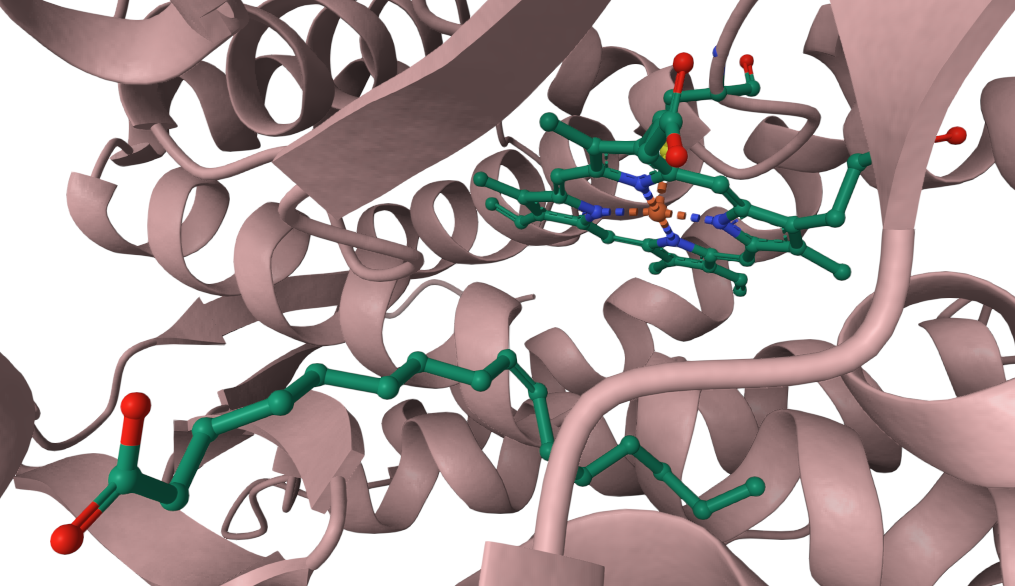

Palmitoleic acid bound adjacent to heme of P450BM3 (Li, H.Y., Poulos, T.L. (1997) https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb1FAG/pdb)

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs) are well established enzymes for performing challenging oxidations: notably including C-H activations, producing hydroxylated products regio- and enantioselectively. So far, the majority of characterised CYP enzymes originate from mesophiles, and display only moderate temperature stability. However, several have been discovered that do withstand higher temperatures; a handful have been reported that retain their function at temperatures greater than 75 °C. Ideally, a thermally stable CYP would be ‘self-sufficient’, meaning an electron transfer domain is joined to the heme active site; otherwise the identification of suitable transfer partners, also thermally stable, that function efficiently with thermophile CYPs is a significant challenge.

Thermostable P450BM3-like oxygenases are a promising target, as these have been investigated in detail. Engineering them to oxidise unnatural substrates (essential for chemical synthesis) is well understood and these methods could be adopted for related oxygenases. Currently, few thermostable enzymes from the CYP102, or similar self-sufficient families have been discovered. Interestingly,Thermosporothrix hazakensis contains a gene encoding an enzyme from this family. The recently discovered, mildly thermophilic bacterium, thrives in the elevated temperatures found in compost, ranging from 31-58 °C. Its P450BM3-resembling enzyme has been demonstrated to oxidise palmitic acid. It should also be self-sufficient, containing a reductase (CPR) domain adjacent to the heme domain.

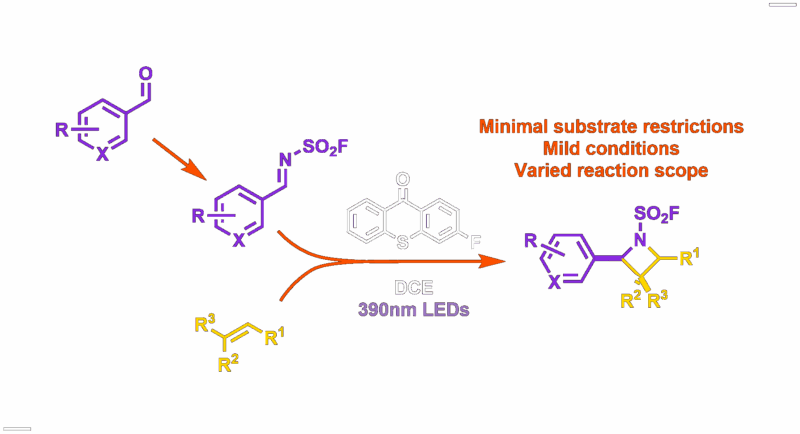

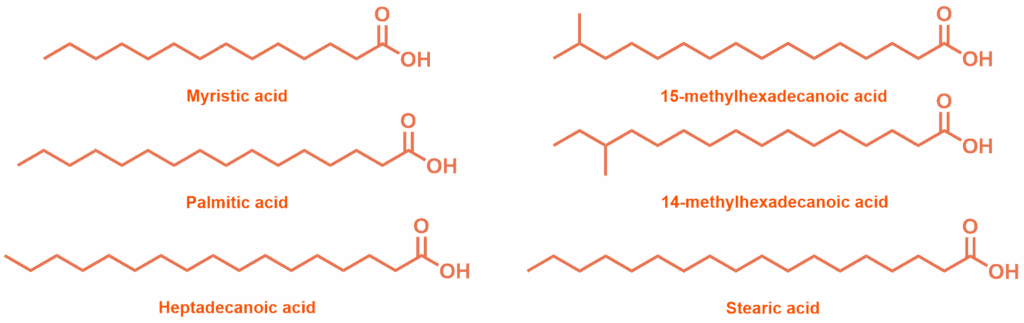

Initial fatty acid substrates screened for binding to WT CYP102 holoprotein

Possible substrates for the wild-type (WT) CYP102 holoprotein were identified through changes in the UV-Vis absorbance spectrum (Soret band): substrates binding close to the heme displace a water ligand, producing a shift in absorbance. The saturated palmitic acid (C16) and margaric acid (C17) induced the biggest shifts in absorbance, while acids with shorter chains, and those with more than 17 carbons showed a reduced effect. Adding methyl branching to palmitic acid, and increasing saturation, also appeared to reduce the binding effect. The accuracy of the UV-Vis proxy measurement was confirmed with binding assays of 15, 16 and 17-carbon chain acids: longer-chain fatty acids bound most strongly, with margaric acid showing particularly high affinity (KD = 0.30 μM). These trends align with P450BM3, suggesting the enzyme has similar physiological substrates.

However, in vitro activity was low compared to P450BM3, possibly due to the loss of FAD or FMN cofactors in purification and after incubating at 50 °C, all catalytic activity ceased. In whole-cell (E. Coli) reactions, yields of oxidised metabolites (predominantly hydroxylation near the chain terminus) increased, once again showing resemblance to P450BM3 with a similar ratio of products. With the WT holoprotein showing a lack of thermostability (despite its origin in bacteria that thrive at 50 °C) and low in vitro activity, but with a reductase adjacent to its heme domain, the heme domain was a good candidate for further investigation. It was converted into a peroxygenase: exchanging the catalytically critical glutamate-threonine (ET) pair adjacent to the heme iron with glutamine-glutamate (QE), as found in the peroxygenase CYP255 family, creating the QE heme domain mutant, dubbed ‘HazakQE’.

The resultant reduced form of the protein responded to carbon monoxide with a comprehensive shift in the Soret band, indicating a functional CYP enzyme. This response was maintained after heating at 50 °C for thirty minutes, with 94% similarity in the UV-Vis region; however, heating to 65 °C appeared to denature it. When treated with H2O2 (2-10mM) at 30 °C degradation of the enzyme was observed, with higher concentrations of bleach accelerating the process. In the presence of fatty acids, the effect is reduced, presumably due to shielding of the heme.

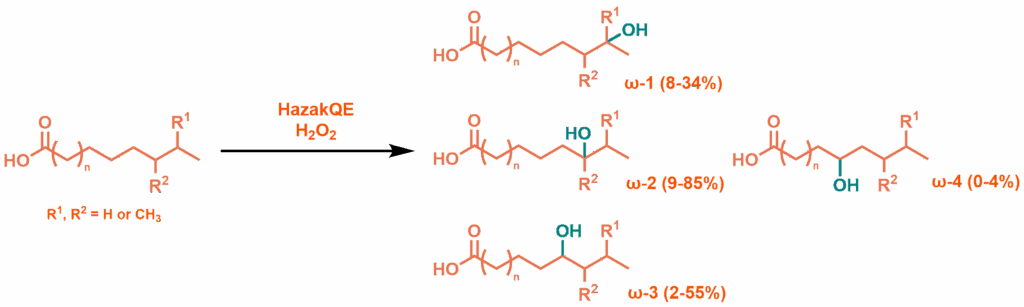

Distribution of hydroxylated products from reaction with HazakQE peroxygenase

Testing the palmitic, myristic, 14-methylhexadecanoic and 15-methylhexadecanoic acids with HazakQE (after a pre-incubation for 30 minutes at 50 °C) and H2O2 confirmed the mutant’s functionality. At low concentrations of enzyme and peroxide, over 30 minute reaction times, the same metabolites produced by the WT holoprotein were observed, in similar ratios. At higher concentrations and reaction lengths, complex mixtures of over-oxidation products were produced, showing that the initial metabolites are also potential substrates for the enzyme and that the turnover number was good: >250 for longer fatty acids, a significant improvement over previously reported P450BM3 mutants. WT P450BM3 denatures at 43 °C, but previously reported efforts to convert the more stable heme domain into a peroxygenase have produced a more stable T268E mutant. Comparison of this mutant, from a less thermophilic origin, with HazakQE reveals equivalent thermostability, with both beginning to show small reductions in activity when heated to 55 °C.

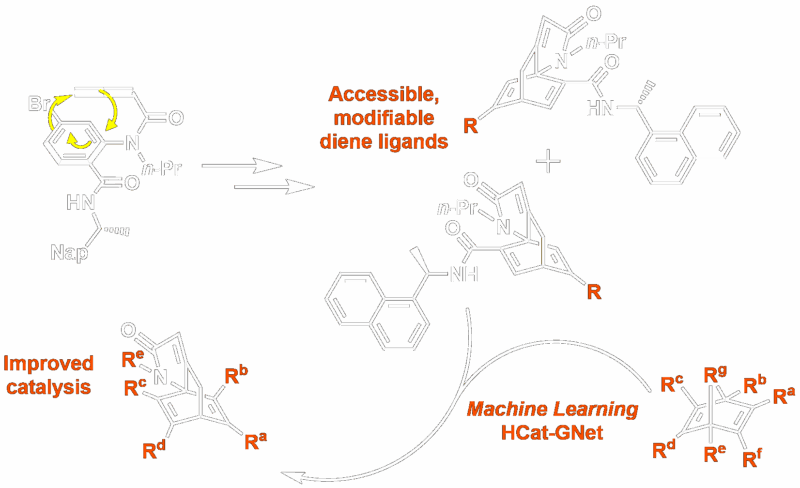

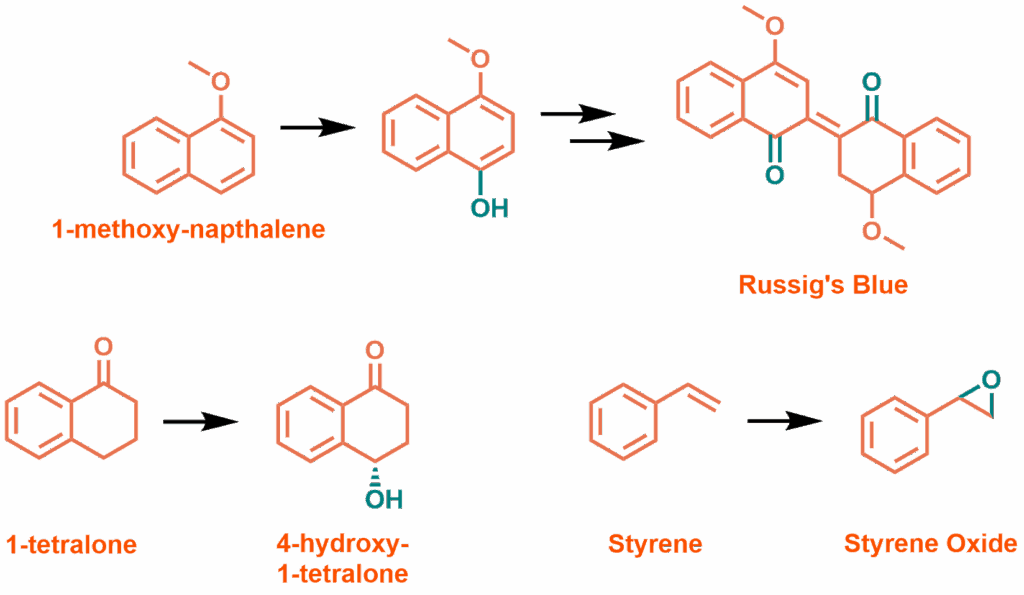

For use as a practical synthetic tool, biocatalytic enzymes need to work on non-physiological substrates: styrene, α-tetralone and 1-methoxynaphthalene are known to be metabolised by other CYP enzymes. 1-methoxynaphthalene is particularly useful for testing enzymatic activity, as the product of its oxidation is the strongly absorbing dye, and therefore easily quantified, Russig’s Blue. This oxidation was efficient at 30 °C and 40 °C (with and without a 50 °C pre-incubation), but at 50 °C was barely functional. While the enzyme should be able to withstand the greater temperatures, the effect of oxidative damage from the peroxide present is probably increased. Oxidation of α-tetralone is similar, with higher temperature reactions producing significantly less product. This reaction was also found to be slightly enantioselective, producing 60% ee of what is assumed to be the S-enantiomer. WT P450BM3 and the derived mutant T268E produce hydroxylated products with a 30% ee. HazakQE oxidation of styrene is essentially racemic, whereas T268E does produce a slight excess of the R-enantiomer. Despite this, yield and turnover are greater for HazakQE (480 μM, 160 TTN vs 360 μM, 120 TTN).

Non-physiological substrates oxidised by HazakQE and H2O2

By characterising a self-sufficient CYP102 from T. Hazakensis and subsequent modification of the heme domain, a thermally stable peroxygenase (HazakQE) was developed. While more resistant to heating than the holoprotein and other mesophilically derived CYP enzymes. While it was not more themostable than the heme domain of P450BM3, HazakQE maintained activity at 50 °C and outperformed existing mutants in efficiency. Furthermore it stands as proof of concept that the simple two amino acid mutation strategy, paired with the accessible screening assay utilising Russig’s Blue, opens the door to faster discovery of robust CYP biocatalysts. Together with earlier work on Fluorochem-sourced styrene derivatives, benzoic acids and their metabolites, HazakQE underscores how accessible molecules enable discovery of robust CYP biocatalysts.

Dr M. Tomsett – Technical Liason Officer

- Podgorski, M. N., J. H. Z. Lee, J. M. Scaffidi-Muta, J. Akter, and S. G. Bell. 2025. “ Characterisation of a Self-Sufficient Cytochrome P450 Enzyme From the Bacterium Thermosporothrix hazakensis and Its Conversion Into a Peroxygenase.” Microbial Biotechnology 18, no. 10: e70234.

- Podgorski, M. N.; Keto, A. B.; Coleman, T.; Bruning, J. B.; De Voss, J. J.; Krenske, E. H.; Bell, S. G. The Oxidation of Oxygen and Sulfur-Containing Heterocycles by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29 (50), e202301371.

- Coleman, T.; Lee, J.; Kirk, A. M.; Doherty, D. Z.; Podgorski, M. N.; Pinidiya, D. K.; Bruning, J. B.; De Voss, J. J.; Krenske, E. H.; Bell, S. G. Enabling Aromatic Hydroxylation in a Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase Enzyme through Protein Engineering. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28 (67), e202201895.

- Podgorski, M. N.; Bell, S. G. Comparing and Combining Alternative Strategies for Enhancing Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase Activity. ACS Catal. 2025, 15 (6), 5191-5210.

- Li, H., Poulos, T. The structure of the cytochrome p450BM-3 haem domain complexed with the fatty acid substrate, palmitoleic acid. Nat Struct Mol Biol 4, 140–146 (1997).

- Salazar, O.; Cirino, P. C.; Arnold, F. H. Thermostabilization of a Cytochrome P450 Peroxygenase. ChemBioChem 2003, 4 (9), 891–893.

- Shoji, O., Fujishiro,T., Nishio, K., Kano, Y., Kimoto, H., Chien, S., Onoda, H., Muramatsu, A., Tanaka, S., Hori, A., Sugimoto, H., Shirob, Y., and Watanabe, Y. Catal. Sci. Technol., 2016,6, 5806-5811